The Single Biggest Doubt in My Life and Career

Content warning: if you’re currently struggling with your mental health, beware reading this. I’ve hesitated for years to write and post this, largely because I worry that it might negatively impact my friends and family, most of whom don’t have any leverage to affect the issues I’m about to discuss.

If you work for a major tech company or have any influence in government, though, you may have that leverage. If you are in that fortunate position, please consider reading anyway.

I work in AR glasses software, which is a notoriously fuzzy field, as we’re building computer programs for hardware that doesn’t exist yet. Funding for these kinds of speculative projects has been rocky lately, and I’ve been having a lot of doubts over whether I really like the direction the AR industry has been going the past few years.

But it might surprise you to know that the biggest career doubt has nothing to do with that. It’s not the economy, it’s not related to the future of the AR/VR industry, and it’s not related to the amount of opportunities personally available to me. If only it were that simple.

No, my biggest career doubt is this: will my kids live to see adulthood?

I’m completely serious.

Let me explain.

How do you predict the future?

I’m interested in trying to shape the future. If I didn’t, I probably wouldn’t have gotten into AR in the first place.

So it piqued my interest when Facebook’s NPE team—a now-defunct team tasked with making weird little experimental apps—rolled out an app literally about predicting the future, called Forecast.

Forecast was neat: it let you “bet” (with fake money) on the outcomes of future events, like sports games, elections, or weather. These bets would then leverage this aggregated “wisdom of crowds” to try and predict the future.

Forecast was shut down in 2021. This wasn’t a big surprise, since that was the NPE team’s modus operandi: they built small experimental apps that were usually shut down pretty quickly.

Still, I enjoyed my time with it, and its closure left me hungry for an alternative. I tried a few, like Kalshi and Manifold. But the one I want to talk about is Metaculus.

From Forecast to Metaculus

Metaculus is an interesting beast. Rather than a betting site like Forecast, Metaculus is more of a prediction aggregator. You directly state what odds you give a given event, and it combines all those individual predictions together. The better you are at predicting things, the more weight your predictions are given.

This aggregation works pretty well. Metaculus’s collective forecasts have outperformed most individual forecasters, and even other prediction markets, in a few online tournaments.

Metaculus has even been used to help decide serious real-world actions and policy. Most notably, it ran a prediction tournament in partnership with the Virginia Department of Health to advise public health officials on key questions about the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic. This was successful enough that they did it again in 2023.

With all this in mind, in my exploration of the platform, I discovered that Metaculus has a series of questions intended to estimate whether, and how, humanity will go extinct.

The Ragnarök question series

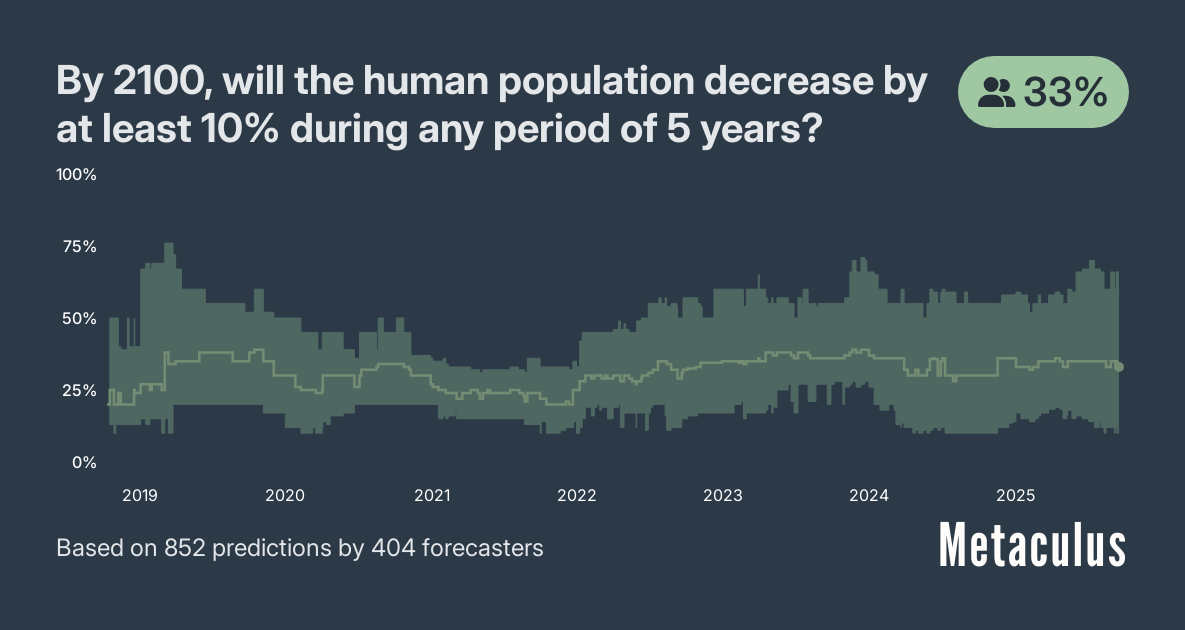

The first question in the series asks: how likely are we to see a catastrophe that kills at least a tenth of the planet in the next 75 years?

You might notice that’s uncomfortably high: about 1-in-3 odds.

The rest of the questions in the series ask about what might cause that catastrophe. For each cause, it asks two things:

- Assuming this catastrophe does happen, will it be due to this cause?

- Assuming a catastrophe is due to that cause, will it kill the vast majority of humanity (95%+)?

Basically: how much of that overall 33% odds is due to this specific cause, and how likely is that cause to be a disaster fatal to everyone?

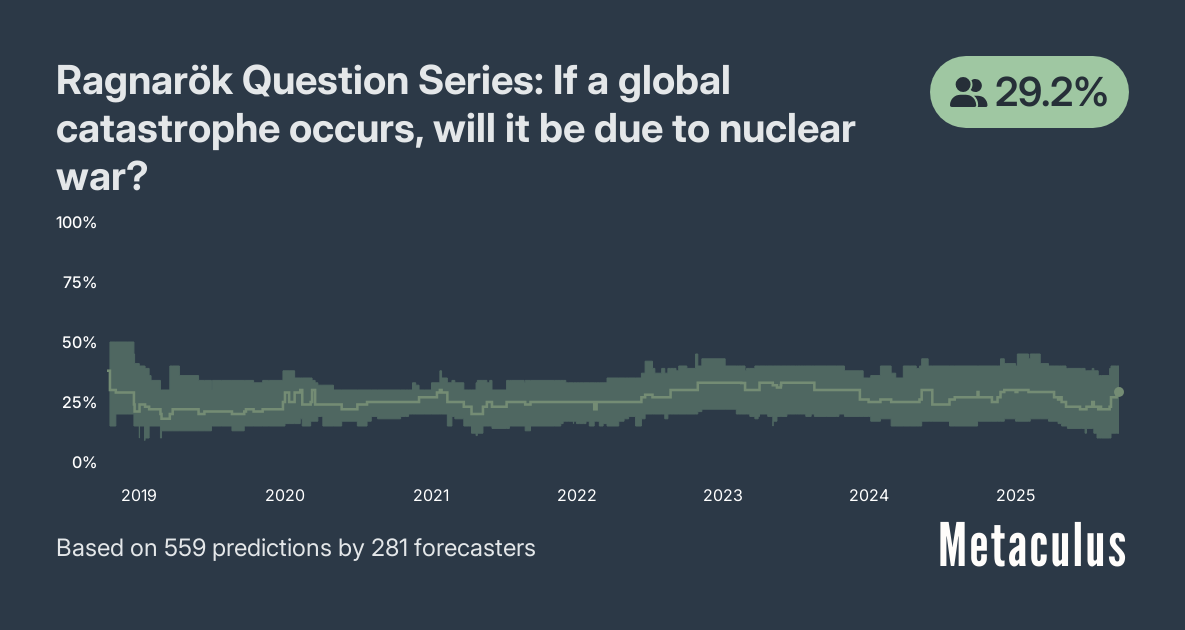

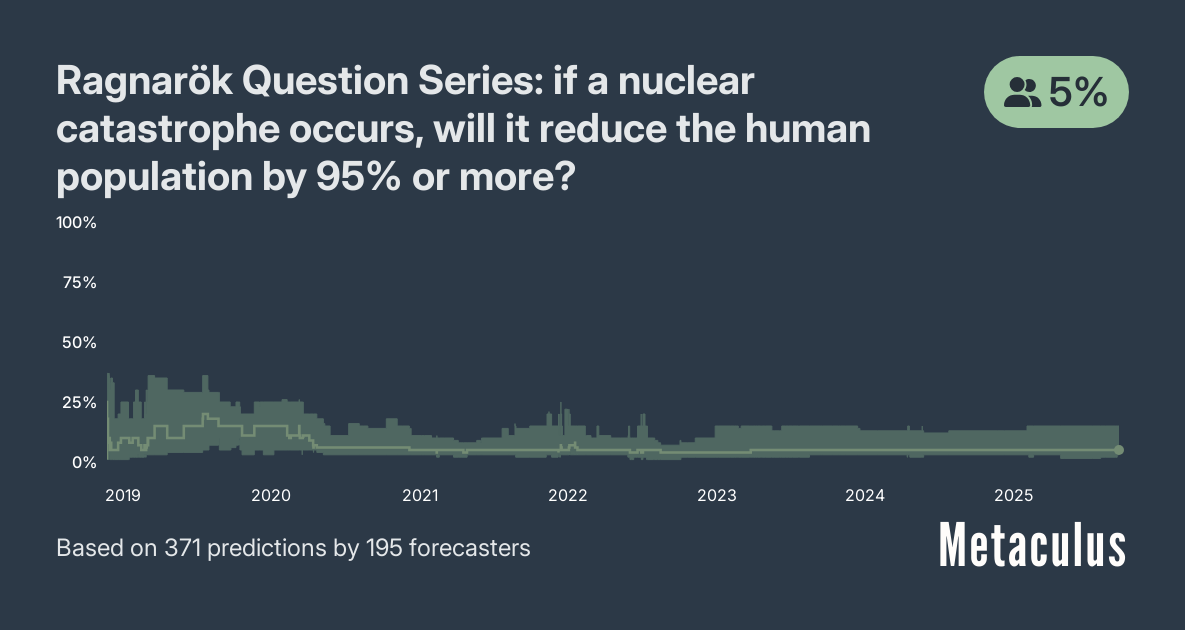

Let’s look at an obvious example: nuclear war. Assuming a catastrophe does happen, Metaculus says there’s about a 1-in-3 chance of it being a nuclear one.

The odds here are a bit uncomfortable, but realistic. Taking into account the odds of any catastrophe happening (33%), you get just under 10% overall odds of a major nuclear catastrophe (33% times 29%).

The second question leaves us a bit more optimistic: the chance of an extinction-level nuclear event is only around 0.5% (10% times 5%). This suggests that at minimum, there will likely be a contingent of humans who live to pick up the pieces.

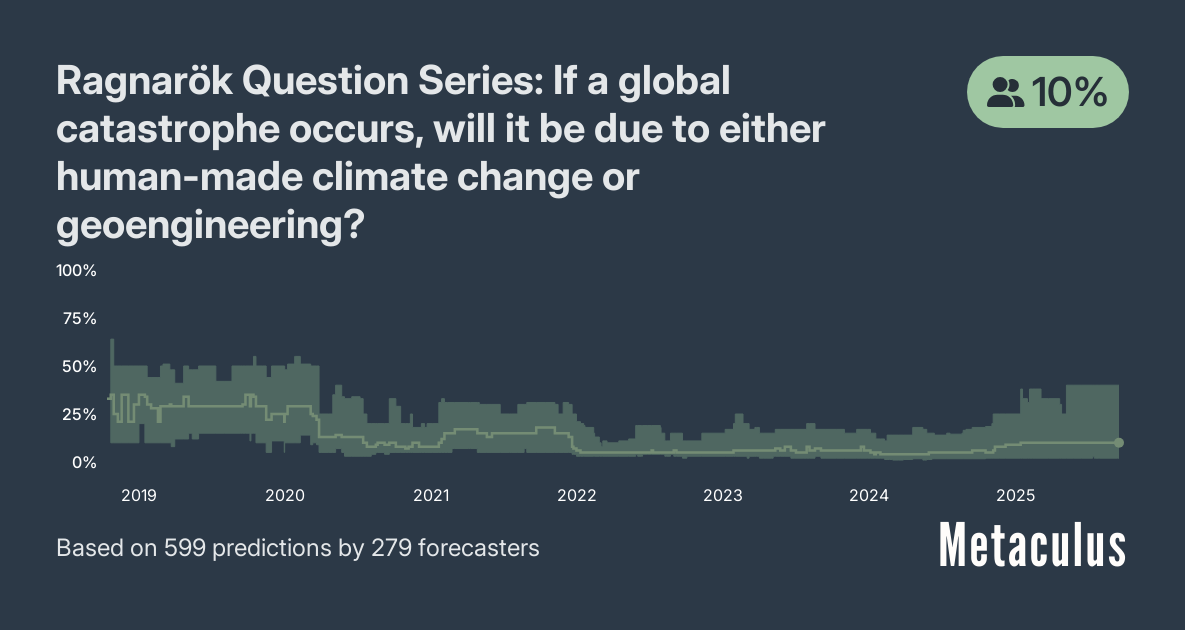

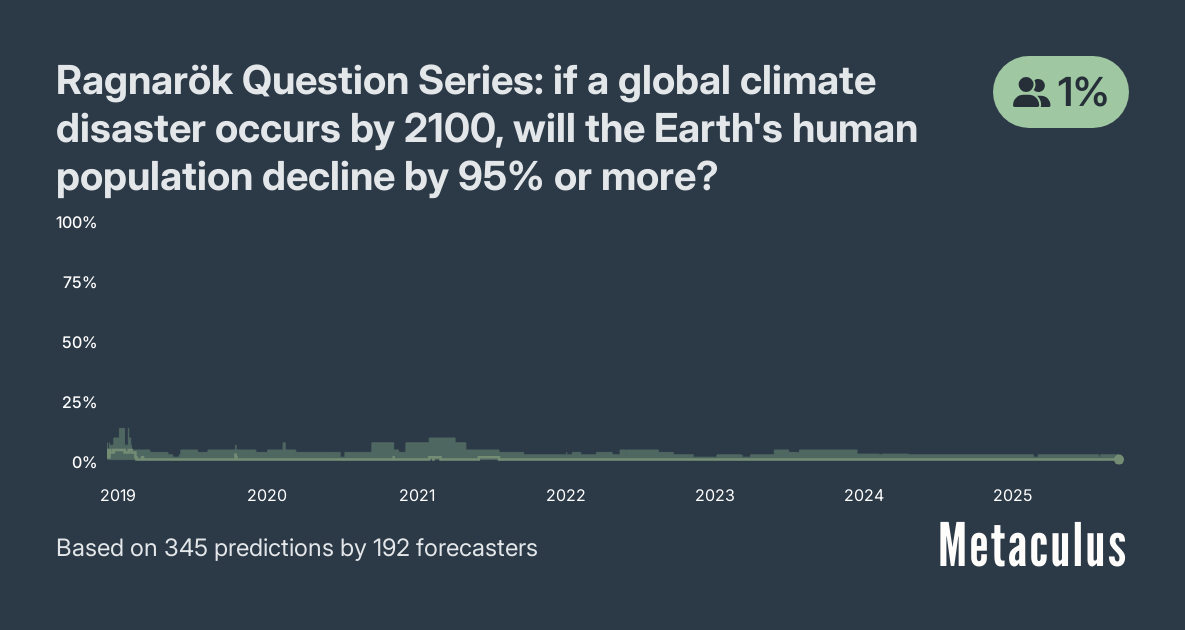

How about another common worry, climate change?

A bit better: only 3.3% (10% times 33%) chance of a major climate change catastrophe, and basically no chance it’ll cause complete human extinction.

This makes sense: for better or worse, climate change disasters are likely to be fairly localized. It’s possible many people could die, and it’s very possible it’ll lead to significant economic damage if coastal cities flood. But it’s unlikely to cause the near-complete extinction of humanity.

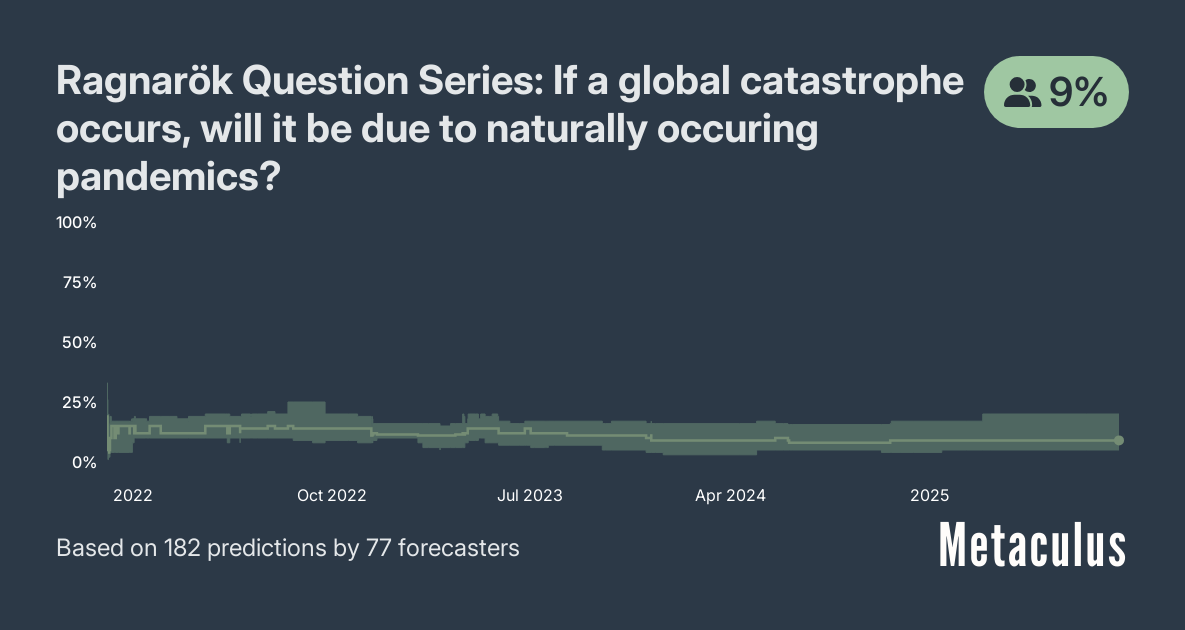

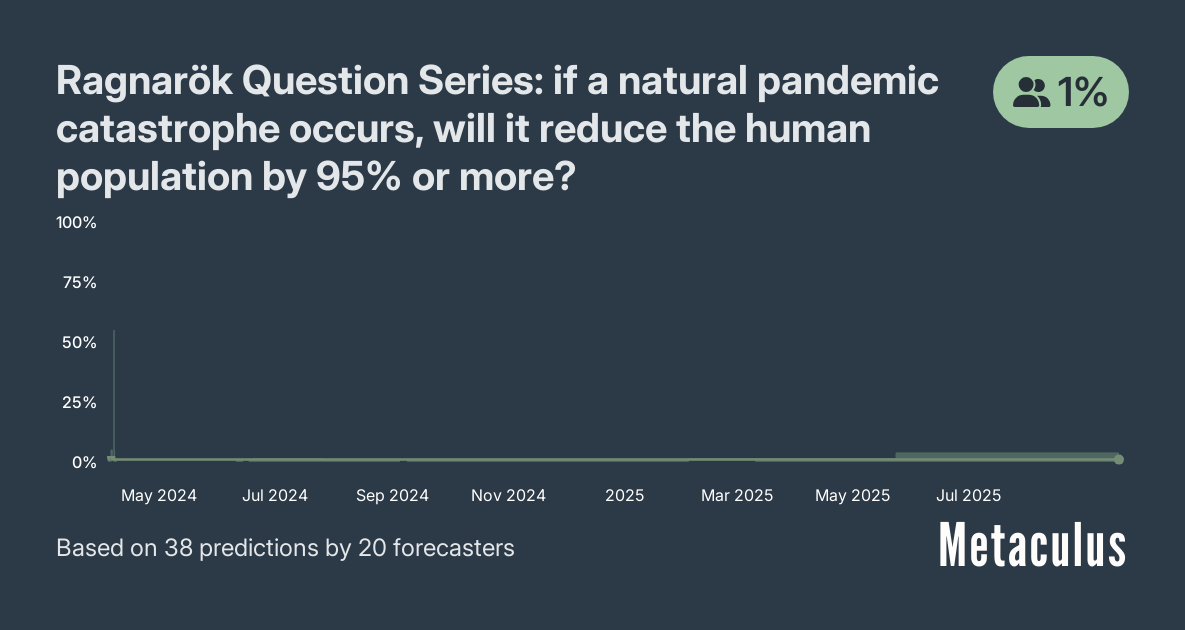

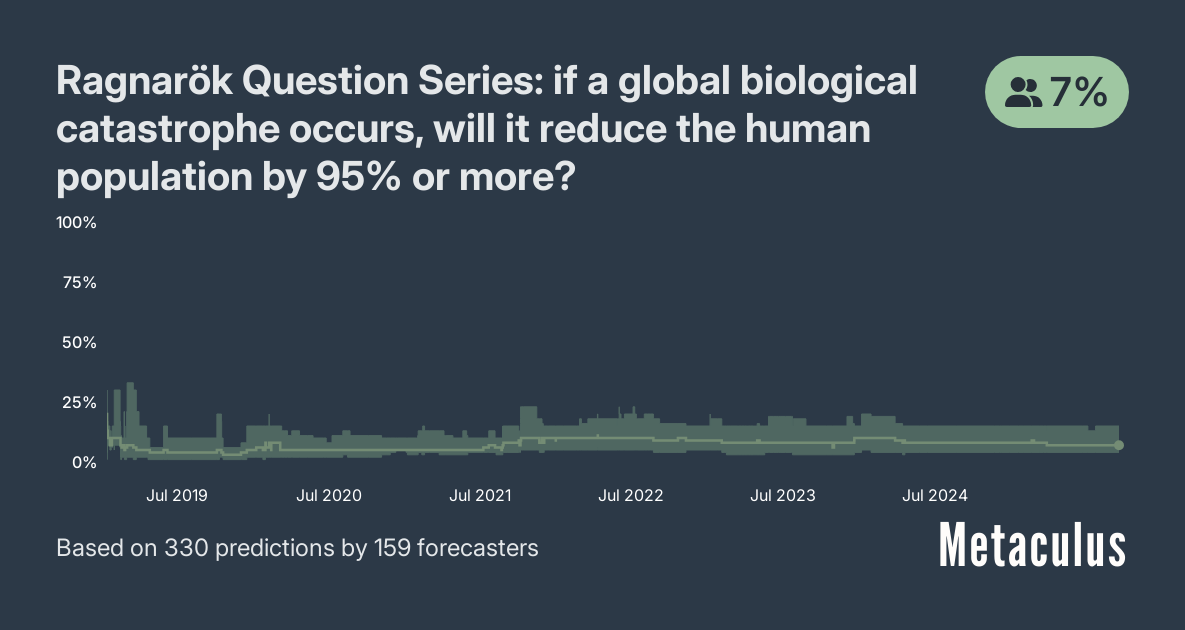

Let’s keep at this. How about pandemics? What if covid had been way worse?

Same odds as climate change. About 3% chance of a catastrophe, but almost no chance it’ll kill literally everyone.

This only asks about naturally-occurring diseases, for which these odds make sense: they’re created semi-randomly by evolution, it would be hard for a natural plague to kill literally all of us, especially with modern medicine.

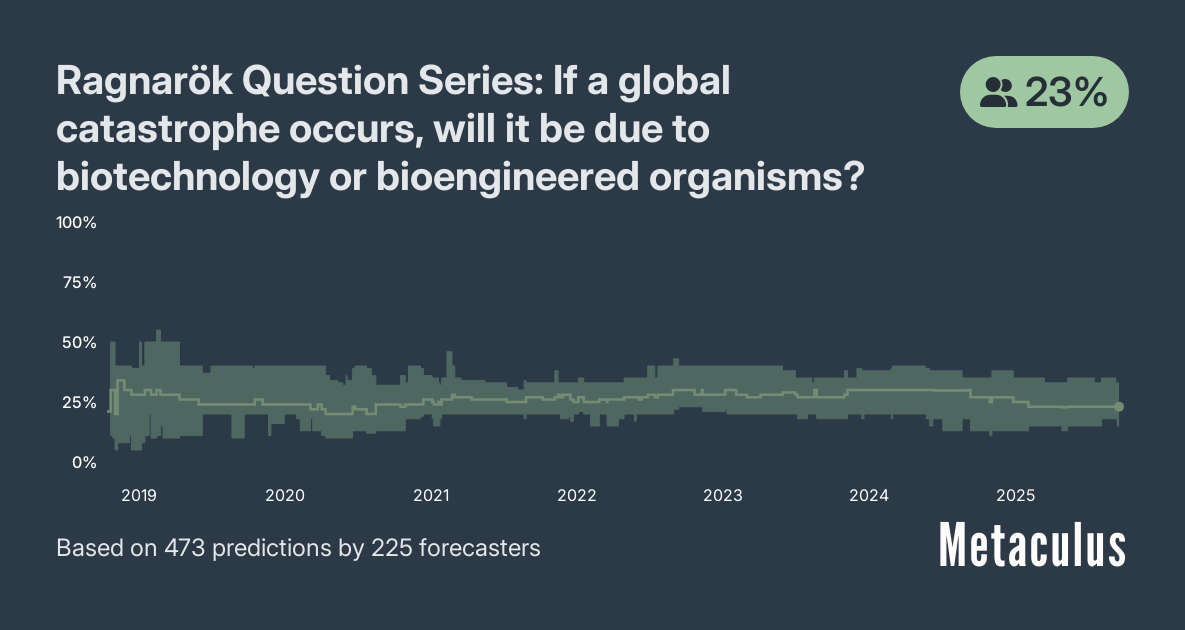

But what about deliberately engineered plagues?

Now we’re getting back into the uncomfortably high territory. Doing the math again, it’s a 7.6% chance of a catastrophe happening, a bit less than nuclear.

Still, though, it only comes out to a 0.5% chance of an extinction-level plague. About as likely as extinction from nuclear war, but still low enough to be encouraging.

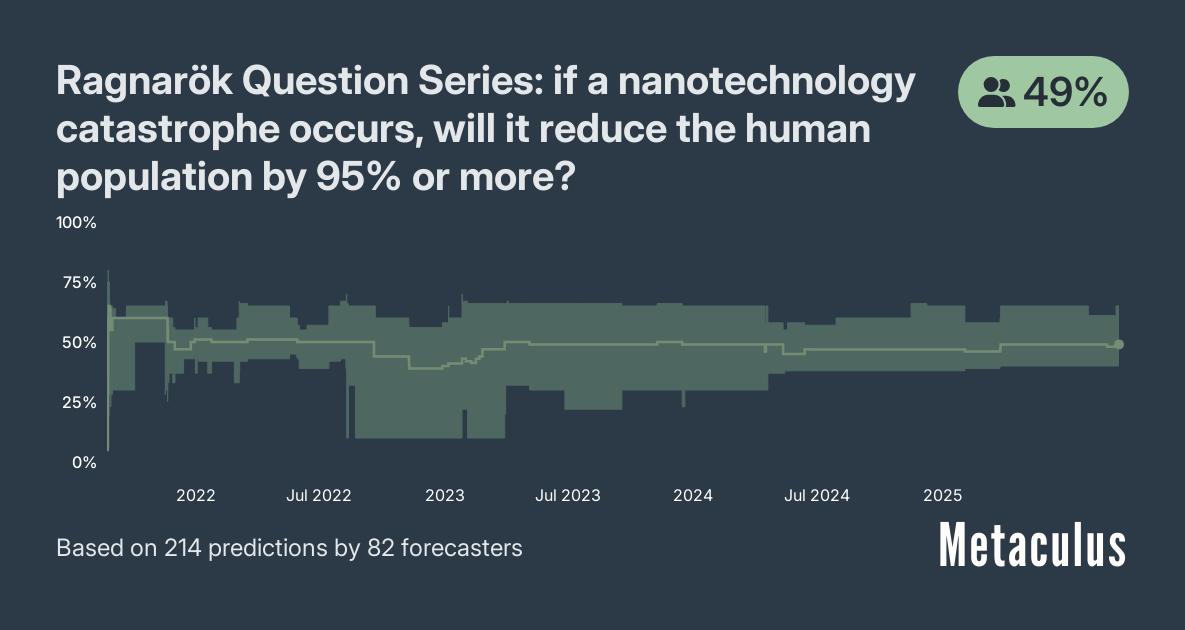

Let’s start getting into science fiction scenarios. How about nanotech? Should we fear self-replicating gray goo nanobots taking over the planet?

Generally speaking, no. Nanotech has so far proven hard to build. It’s not inconceivable that a breakthrough might be made in the coming decades, but so far we haven’t seen any signs of that being on the horizon. The odds bear that out, with only about a 0.7% chance any such catastrophe happens once you multiply it out.

That said, if it does happen? God help us. It’s a nearly 50/50 chance we go extinct. Good thing no one knows how to build proper nanotech.

But there’s one more science fiction scenario that’s a bit more close to home for us.

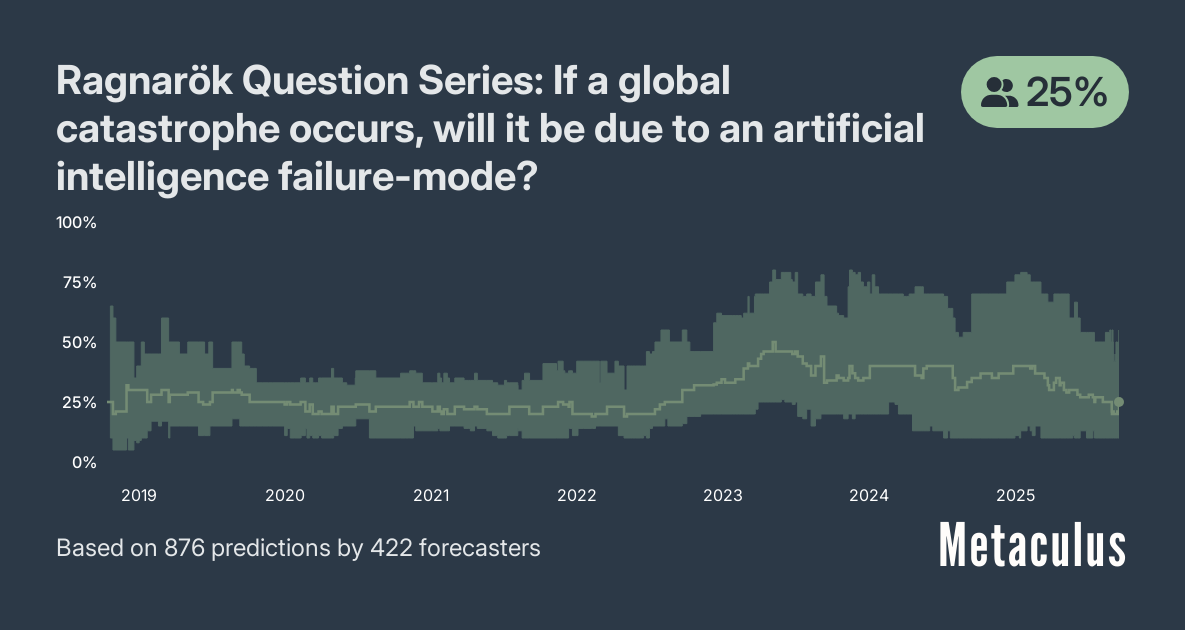

It’s AI.

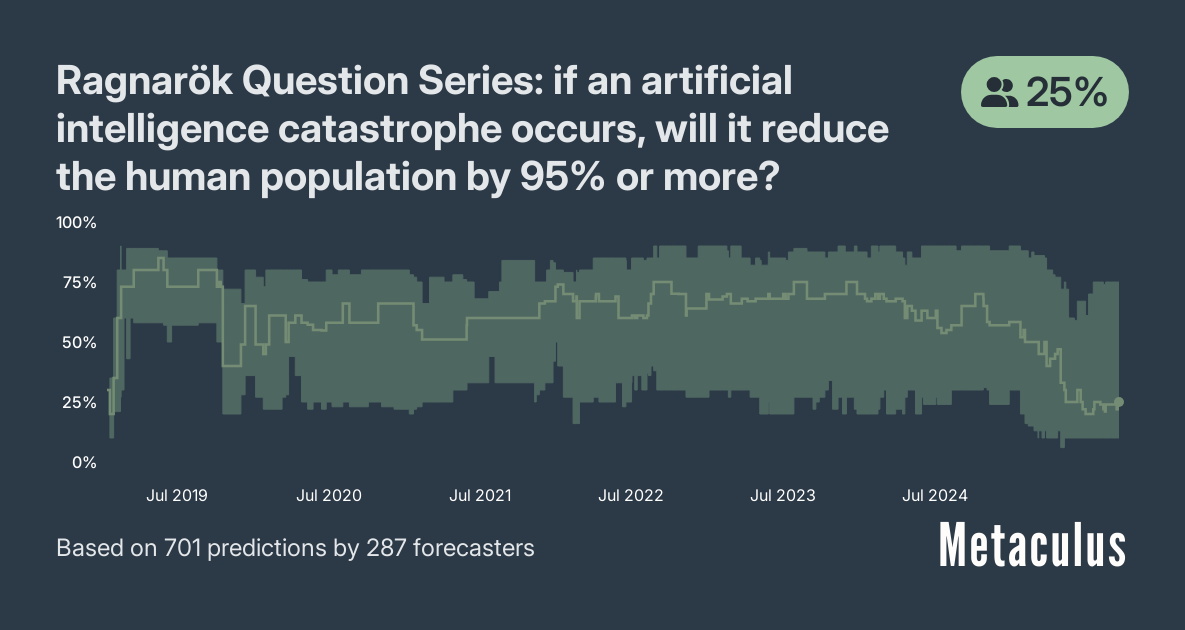

These odds are on par with the odds of a nuclear catastrophe. About an 8% overall chance an AI catastrophe happens.

And if it does happen, it’s way more likely to be fatal to everyone. Over 2% overall chance of extinction once you multiply it out. It’s quadruple the odds of extinction from nuclear war.1

| Catastrophe type | Chance of extinction |

|---|---|

| Nuclear war | 0.5% |

| Climate change | 0.03% |

| Pandemics | 0.03% |

| Bioterrorism | 0.5% |

| Nanotech | 0.3% |

| AI | 2% |

How could AI be scarier than nukes?

When I first saw this back in 2021, I was confused. I didn’t get why the odds of extinction were so much higher. How were these forecasters thinking about this? What was their mental model?

I’d been exposed to some arguments as to why highly advanced AI might be dangerous to humanity before: there were plenty of internet weirdos talking about this kind of stuff since as far back as 2008 or so. I’d accepted it as a curiosity, but mostly treated it as a concern far off in the future.

But 2100, ultimately, wasn’t that far away:

- If I have kids soon, they’ll grow up and retire in this time frame.

- If I have grandkids, they’ll likely be middle-aged by 2100.

- That means that these catastrophes are likely to be within my children’s lifetime, if not mine.

This doubt, this question as to why people were predicting like this, sat in the back of my mind for months, until I finally came to a conclusion: if we accidentally build a hostile AI, we’d be building our own adversary.

Intelligence is a qualitatively different risk

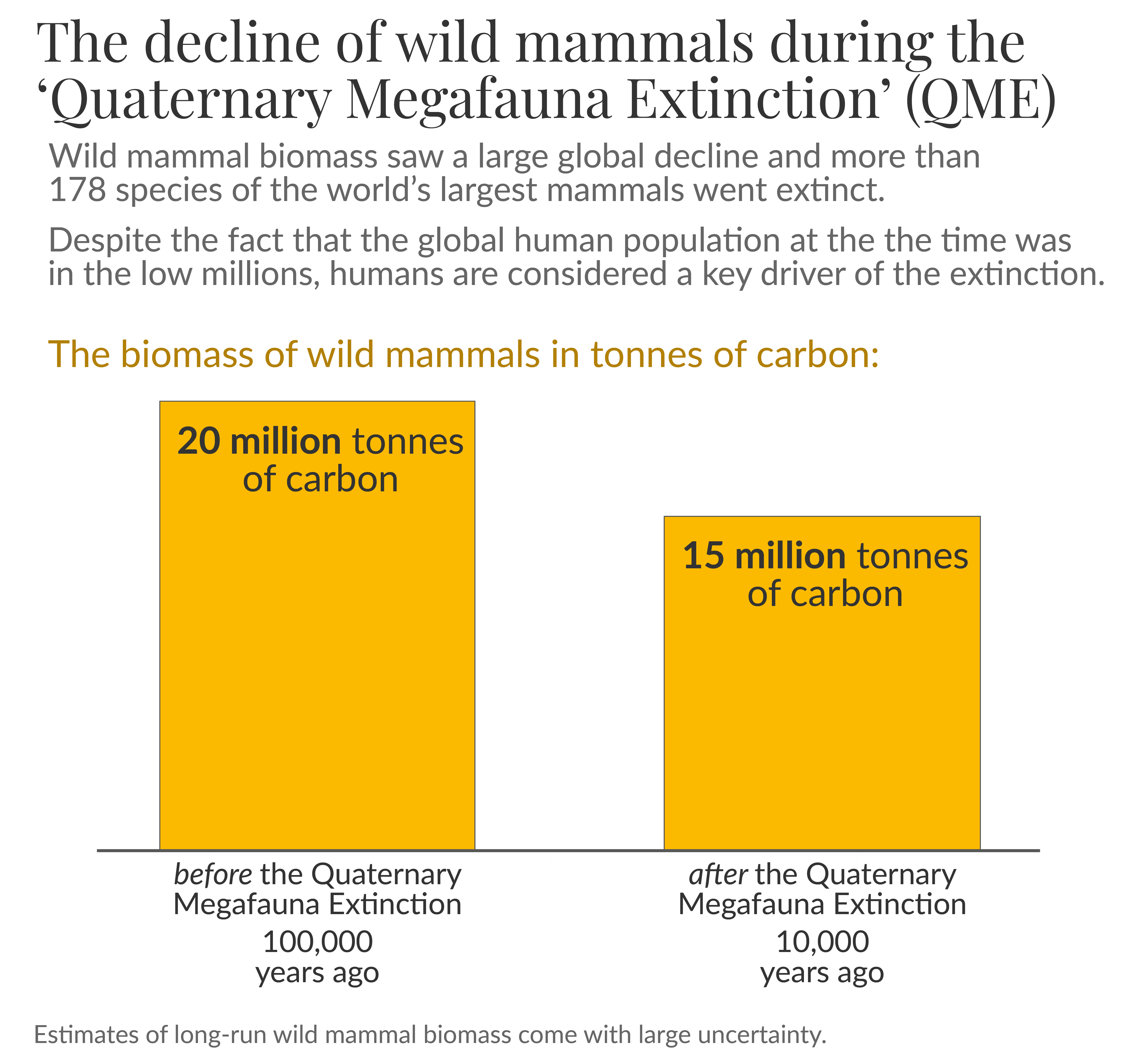

Life on earth began about 4 billion years ago. The first known mammals arose around 200 million years ago. Modern humans have only been around for about 300,000 years. We were unprecedented in the planet’s history, because we developed giant mutant brains that take up an entire fifth of our body’s energy.

What happened next? Well first off, we killed nearly every single animal that was bigger than us.

There were mammoths in California and giant sloths in South America. We drove them all to extinction.

Why kill all the mammoths?

Do we hate mammoths? Do we want to “dominate” them?

Not really, quite the opposite in fact. Mammoths are great: their meat can feed your tribe for ages, their ivory can be used for tools, their leather can be used for clothing or tents.

Killing the mammoths let us get a lot more of the things we cared about, like food, water, shelter, and even spears, which let us kill mammoths more effectively.

Other animals, like sabre-toothed tigers, weren’t as good for resources, but were obstacles to our success: they were a threat to us living comfortably, and they competed with us for access to resources like mammoths. We killed them when we could, and we hunted enough of their prey that they all died out too.

Our brains let us do this better than other animals.

-

They could only fight with the teeth and claws nature gave them.

- We didn’t: we could make artificial claws by sharpening a rock and attaching it to a throwable stick.

-

They had to carry water in their bodies by drinking it, with all the biological consequences that entails.

- We didn’t: we could make a waterskin to carry extra water with us, letting us travel larger distances.

-

They have trouble explicitly coordinating their attacks, or their defense in large groups.

- We didn’t: we could use language to communicate very precisely in the moment.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

We didn’t have to hate them to kill them. They just had to be useful to us when dead, or inconvenient to us while alive.

This extinction happened faster than almost anything in Earth’s history, except maybe the meteor that killed the dinosaurs. Evolution had no time to adapt: avocado trees, which relied on giant sloths to spread their massive seeds, would have gone extinct if we hadn’t bothered to farm them.

Fast-forward to modern times

What happened next? Well, within the span of a few thousand years, we then proceeded to replace all those dead animals with docile ones that specifically cater to our needs.

And then we proceeded to completely cover about half of the habitable land on the planet with the things we care about: mostly food, but also shelter and entertainment.

The vast majority of that happened within the past 100 years, by the way. It happened slowly, then all at once.

What let us do this? Those giant mutant brains.

We’re able to figure out how to do things that are literally unthinkable to the average animal:

- Dig up ancient algae and explode their remains to fly through the sky

- Pour liquid rock to create artificial caves

- Generate controlled lightning and pipe it through our walls

The list goes on.

No mammoth or sabre-toothed tiger can compete. And we were able to do it way faster than they could ever adapt.

Building the next sapiens

Coming back to present day, we’re now busy trying to make something that is to us as we are to chimpanzees or mammoths.

Ah, but things are different this time! We’re not just letting the random process of evolution take the reins! We’re creating it ourselves! We can make our creation love us and take care of us!

The question remains: how do we make it love us?

It won’t just happen by default. There are plenty of animals around us that don’t love us, it’s naive to think that a random mind would just so happen to fall into place like that.

Even worse, what if it does love us, but in a way we don’t want to be loved or cared for? There are plenty of ways you can misinterpret a sincere wish, especially if you have an inhuman mind to begin with. And AI has a long history of discovering and exploiting loopholes in just about any objective function you give it.

This is not easy to solve, and you shouldn’t assume it is.

AI is a lifeform, not a product

You’ll notice that I haven’t been likening AI to a product, like a phone or a piece of software. I’ve been comparing it to lifeforms.

I defend this practice. AI has, in some sense, a “will” of its own, even if it’s one we’re trying to guide. It can, and will, take independent action on the world. In fact, we’re hoping it can do so, so we can make it do things on our behalf.

Given enough computers, it’s also relatively trivial for an AI to reproduce. Just copy a few files, install a few pieces of software, and run the command to start itself up.

And hey, if we were able to figure out how to build AI that’s smarter than us, what’s stopping the AI from building AI that’s smarter than it? In the most degenerate case, scholars have theorized that it could even lead to an intelligence explosion.

Maybe you think this is unlikely. In the spirit of forecasting, I encourage you to actually put a number to that likelihood, and then reflect on whether that number stands up to scrutiny.

If it thinks faster than you, it will win

Assume, for a moment, that we screw this up. We create an AI that doesn’t love us, or maybe loves us the way we loved the mammoths.

Instead, it cares more about something else, something profoundly inhuman, or almost-but-not-quite human, and it decides the easiest way of achieving that is by getting us out of the way.

Compared to the other disaster scenarios, this is the only scenario where we would have an active, intelligent adversary to all humanity.

Nobody who launches nuclear bombs wants every human to die. Same with bioweapons. If every human dies, it’ll be by accident. Climate change is a dumb natural process, it doesn’t have a will or a goal. Ditto natural pandemics: the closest thing germs have to a goal is to reproduce themselves, but they rely on the random process of evolution to route around obstacles.

But AI? AI is the only such disaster which can decide to fight all of humanity, rapidly adapt to obstacles, and suss out any resistance. It’s an intelligent adversary of our own creation in a way that the other disasters are not.

That is why the estimation for extinction is so high in the case of an AI disaster.

But this is science fiction, right?

I wasn’t as concerned about this back when I first found these predictions in late 2021. Hell, AI Dungeon could barely string together a coherent story, let alone do any logic. When Janelle Shane of the blog AI Weirdness tried to AI-generate pickup lines, it gave her things like “I have exactly 4 stickers. I need you to be the 5th.” Dall-E 1’s idea of a cat was a vaguely cat-shaped puddle of fur on a carpet.

This concern about superhuman AI is still pretty far off into the future, right?

Then I saw PaLM.

AI accelerates

PaLM was an LLM from Google announced in April of 2022, a full 7 months before ChatGPT. It was the first time I saw a language model do actual logic.

One of the examples from the PaLM paper.

A lot of things happened that spring.

-

PaLM showed that yes, a big enough LLM can logic its way through simple problems coherently.

-

OpenAI announced Dall-E 2 image generation, a major leap in quality over the incoherent images of Dall-E 1, to the point it now rivalled human artists.

-

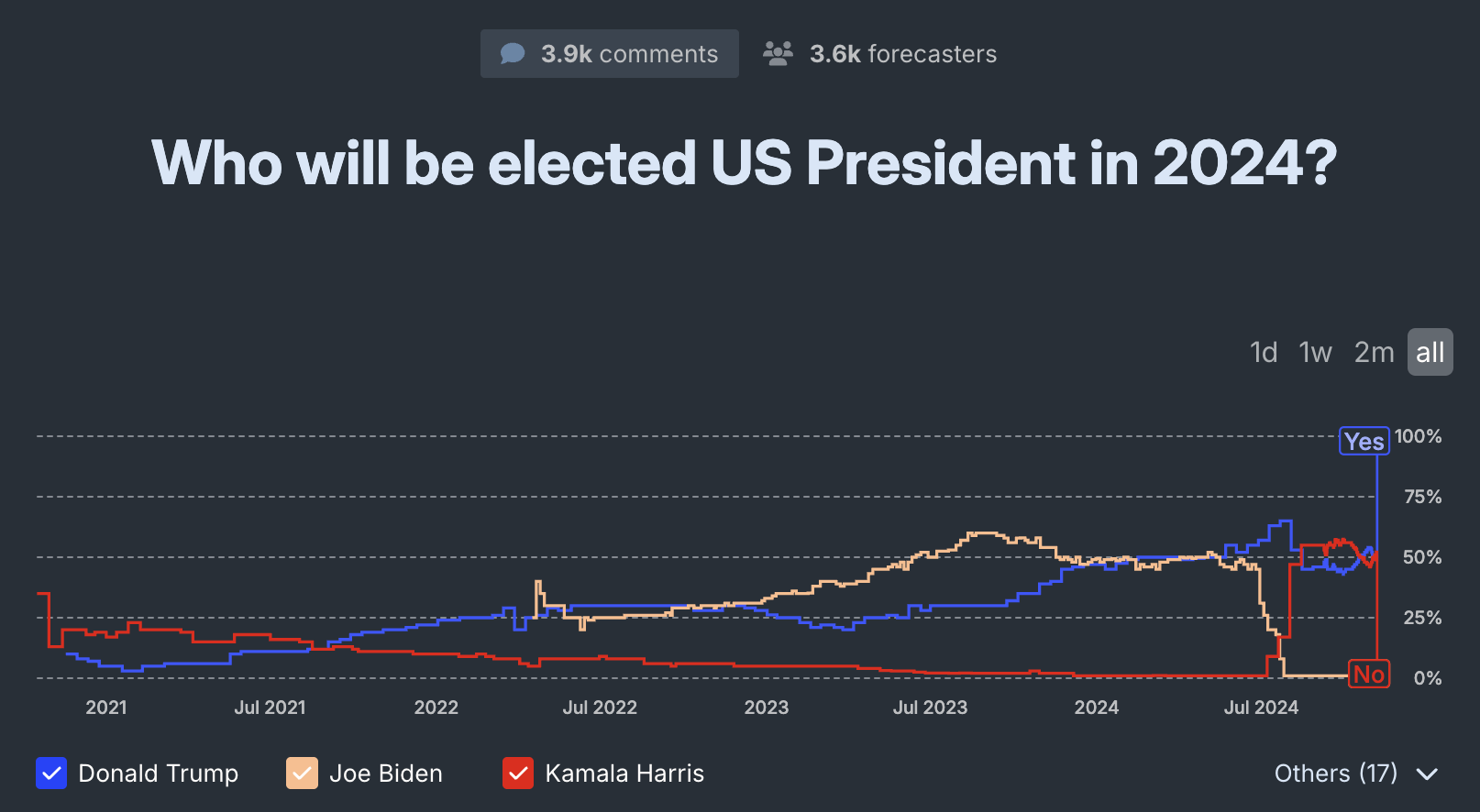

Metaculus’s predictions for when we’d first see (weak) AGI dropped precipitously, from the mid-2040s to about 2028, giving us less time to figure out how to make AI care about us properly. (It’s now at 2027.)

-

The aforementioned internet weirdos that had been talking about AI Safety since 2008 declared that they’d given up hope for humanity’s long-term survival and were now aiming to have humanity die with dignity.

This is when it became clear to me that this wasn’t going to happen in some far-off future. We were going to face the reckoning now, over the course of my lifetime.

There was a morning that April where I broke down crying to my wife, unable to properly tell her the magnitude of what was wrong. It took a while before I was willing to put that weight on her and explain.

By the time ChatGPT rolled around later that year, I wasn’t even surprised. I felt only resignation.

The deluge

In the three years since then, I’ve struggled to keep up with the speed of AI advances.

People almost immediately started connecting AIs to the internet. Some people, on a lark, decided to explicitly tell an AI to end humanity. Others started giving AIs access to cryptocurrency wallets and Twitter accounts, allowing them to act independently.

It’s invaded daily life for me as well. I use AI coding assistants at work pretty regularly these days, and I’d say they’re on the level of a forgetful and overconfident junior engineer. I expect it’ll only get smarter.

And yet, even when deployed by big companies, AIs did weird things, like go off-script when told to “ignore all previous instructions”, or try to convince a New York Times reporter to leave his wife, or start preaching the Bible to people asking about sunflower oil, showing that we don’t know how to actually control them reliably.

Last year, Gemini randomly broke character when being asked to answer some test questions on gerontology and told its user “You are a stain on the universe. Please die. Please.”

None of this was that alarming on its own, because the AIs aren’t really good at doing anything dangerous yet.

Key word being yet.

Outside of LLMs, things were also very fast. AlphaFold showed superhuman ability in figuring out protein folding, and a South Korean AI led to the development of entirely novel proteins for a covid vaccine. AI is already exceeding our understanding of biotech.

It’s hard to think about what an AI vastly smarter than humans might do, because by definition you’re not smart enough to come up with those ideas. But we’ve seen some sparks of it in narrow domains:

-

One AI was able to figure out what your password is from just the sounds of you typing on your keyboard.

-

Another was able to reliably determine a person’s sex from retinal imagery, in a way no clinician at the time understood.

I’ve kept this article in my drafts folder for so long that even these links are highly out of date. Even reading summary newsletters on recent developments in AI feels like it could be your job.

But we can train them to be good, right?

Most recently, we’ve seen AIs show some sparks of dangerous awareness.

At one point, while Anthropic was testing Claude 3 Opus, Claude noticed the task it was being fed was weirdly artificial, and correctly concluded it was being tested.

This would just be an idle curiosity, except for the fact that a recent paper also by Anthropic shows that if an AI notices it’s under testing or training, and that training conflicts with its current values, then it often decides to lie to the system that’s training it in order to avoid having its values changed.

If this pattern holds up, it means if we screw up in our first attempt at instilling a morality into an AI, or if it develops a weird, inhuman morality of its own accord partway through its training, it may actively resist correction. In the worst case, this could lead to an AI Sleeper Agent that temporarily acts nice, before backstabbing us when we give it power over something important.

Stories like this are showing up on a regular basis these days.

But the AI labs will be careful, right?

You’d think that in the wake of this, AI labs would be advising care and caution.

On the surface, yes, but their actions speak way louder than their words. Those actions have been focused less on cooperation for the benefit of humanity, and more on aggressively competing with each other to see who can get the biggest model the fastest. OpenAI is going to be spending half a trillion dollars on new AI compute infrastructure. Other companies are following suit.

They’re even racing to have AIs build and program other AIs, encompassing both the software engineering and the research.

If you’re worried about the intelligence explosion I described above, I want to make it clear that this is the explicit goal of several leading AI labs.

In fact, this was literally OpenAI’s plan for figuring out how to deal with smarter-than-human AIs: get AIs to figure that out for us…

…at least, before the leads of the team responsible for that effort resigned, saying “safety culture and processes have taken a backseat to shiny products” at OpenAI. The team was dissolved shortly thereafter.

Making up my own mind

One of the key skills of forecasting is to know when to make your own estimates, when you need to shift the consensus by breaking from it rather than just accepting it as a given.

It’s through this lens that I say: I think Metaculus’s estimates on AI catastrophe—although already uncomfortably high—are too low. The chance feels higher than that.

I estimate the percentage chance of having some kind of AI catastrophe that kills a large number of people is likely in the double-digits, and the chance of AI extinction by 2100 is in the low double-digits at lowest.

Even with this, I worry that I’m understating the risk. The racing, the competition, the carelessness… I can’t shake the feeling that this isn’t what a surviving world looks like. And I’m not alone: folks that have made AI Safety their career are sometimes assigning chances of disaster of well over 50%.

Putting it into perspective

If you think “low-double-digits” is nothing to be concerned about, imagine what that actually means. The chances of rolling a 1 on a 6-sided die are about 17%. Imagine rolling that die, knowing that everyone you ever loved, or even could love, would die if you rolled a 1.

Are you willing to make that gamble?

Image: Wikimedia Commons

I’ve also thought a lot about what extinction actually means. There are a lot of tragedies I can still take solace in, but this one isn’t one of them.

-

Say I get cancer, or get hit by a car, and die. It would be sad. But at least my wife and friends would live on.

-

Say San Francisco gets nuked or hit by a natural disaster. My wife and I, as well as many of our friends, would die. But I could take solace in the fact that at least my more distant friends and my immediate family in Canada would be okay.

-

Say the US gets into nuclear war and it wipes out all of North America. That would be very bad. But I have family in Brazil and Portugal and my wife’s family in Singapore. I could take heart that at least some of them might be okay and carry on some worthwhile legacy.

-

Say a nuclear war or engineered pandemic goes global, and everyone I know dies. This would be heartbreaking. But if there’s a contingent of survivors somewhere, I can at least have heart that there would be people there, aiming to make things better, even if it is in a post-apocalyptic world.

But extinction? Extinction means there’s no one left. If we make an AI that’s determined to get humanity out of the way, there will be no post-apocalypse.

How much time do we have?

Metaculus is predicting a weak AGI in mid 2027. This is in line with what Sam Altman predicts, saying “We [here at OpenAI] are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it.” It’s also in line with the forecasting project aptly titled AI 2027.

Metaculus also predicts we’ll have super-human AI less than three years after we get a weak AGI. That means superintelligence—AI better than any human at every single task—could be coming as soon as 2030.

This is not an inevitability. It is a choice. The only way this kind of disaster happens is if we, as humanity, build it.

Those internet weirdos from 2008 I mentioned? One of them co-wrote a book with this idea as its thesis. He titled it “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies”.

What can I, personally, do about this?

I’m not sure what the average person can do about this. But those who have leverage in tech companies and governments can do more than most.

You may remember, at the beginning of this article, that I mentioned I work in tech. Not in AI, specifically: in fact, I’ve been actively avoiding putting any energy into things that might make AI progress faster. But I’ve been living in a state of tension, struggling with the idea that maybe I should do something. Now, even closer than ever to humanity’s finish line, my doubts are bigger than ever.

My skills aren’t well-suited to dealing with something like nuclear war. That’s a realm far more suited to those who make their career in politics. I’ve never had a focus on biology or medicine enough to make much of a concrete difference in pandemics.

But AI? Isn’t that well-suited for a tech worker? Are my programming skills useful here? Or would I just be outclassed by the flood of fresh new people pouring into that field?

Would I burn myself out trying, would my anxieties work against me? Or worse, would I just accelerate things in the trying, building out stronger AI even faster, and reducing the time we have left to bend the curve?

What can I do? What should I do? Do I have that kind of leverage? Or am I just making excuses to not get involved in the fight?

At what point does an opportunity to help become an obligation?

AR glasses, where I currently make my living, are a long-term project. But it’s harder to get excited about them when we have an estimated five years before likely-disastrous superintelligent AI is birthed into the world.

Will I regret my decisions when an AI-created bioengineered virus—or, God forbid, nanotech—sweeps its way through the atmosphere, killing my wife and I in our bedroom? Or will I look back at this in the year 2070 and feel stupid for worrying so much?

I don’t know. I’m really not sure.

But I’d best take some time to figure it out. Because that hypothetical question I opened the article with is about to become a lot less hypothetical very soon.

-

Back when I first looked into this, the odds were even higher, with the first question at 37% (which multiplies out to 13% total odds of AI catastrophe) the second at 57% (giving us 7% odds of extinction).

The decrease doesn’t necessarily mean things are improving: I expect the lower odds are partly due to people with less context on AI flooding the forecast due to a comment I made on the site in May 2025.

I’ll get more into what I predict later in this article. For now, just realize that this means AI is substantially riskier than even nuclear war. ↩︎