A Tech Worker's Guide to Interest Rates

Over the past few years of tech industry ruin, I’ve had friends and family worriedly ask me and my wife how our jobs have been going. “I’ve been seeing news of layoffs,” they say. “Why is it that almost every single tech company seems to be tightening its belt, cutting costs, and laying people off all at once?”

Among other causes, I usually mention government interest rates. And I’m sometimes met with confusion: “What do interest rates have to do with it?”

Discussions about interest rates on Hacker News, a popular online forum for techies.

Online, people also bring up interest rates. They say low rates means “money is cheap”, or that the craziness of the 2010s—where money flowed into weird startups, crypto, and NFTs—was a “ZIRP”: a Zero Interest Rate Phenomenon.1

But I find explanations of this are often aimed at people who already have some sophistication in finance and investing.

So let me give it a shot. I’ve come up with a standard answer for friends and family, and I may as well write it down.

Background: risk vs. return

Picture you’re an investor with some money burning a hole in your pocket. Where do you invest it?

The answer depends on how willing you are to lose that money. Riskier investments have a better chance to pay off, but also have a higher risk of losing you money.

Government bonds

The safest thing you can do with it is loan it to a government of a big, rich, stable country like the US. If the US government were to fail to pay back its debts, you’d have way bigger problems than the loss of a few investments.

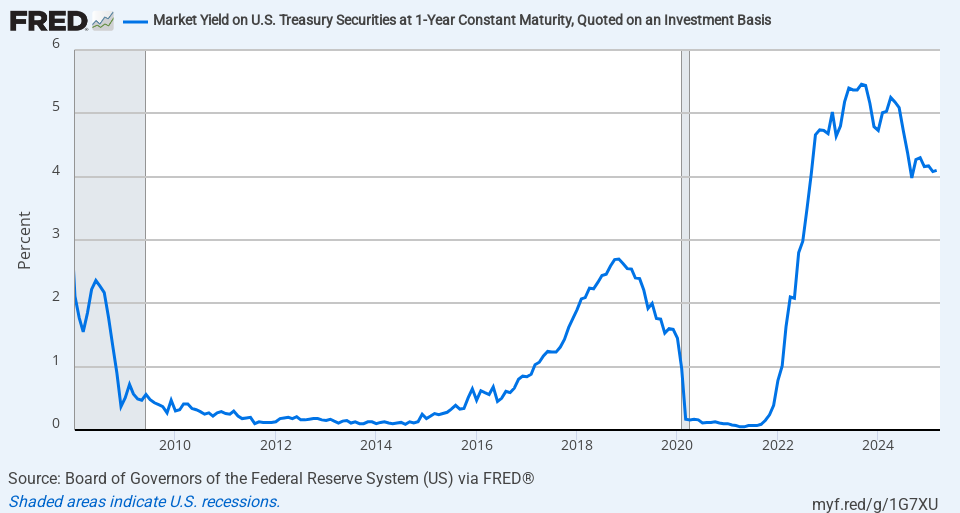

Because it’s so safe, the payoff is low. Right now, the US gives you about a 4% per year return on your investment, but that’s unusually high for recent decades: back in the 2010s, the rate was actually around 0.15%.

Corporate bonds

Want more risk and more earnings? Loan money to a big company instead.

Companies are more likely to go bust than the US government, so they have to offer you a better deal. For example, Toyota is willing to give you about a 5% return.

Loaning money to big corporations like this isn’t too unsafe, because if Toyota were to go bust, the bankruptcy judge would force them to sell off everything they own and use that money to pay back their loans. You’d hopefully get back at least part of the money you lent them.

Though Toyota going bust doesn’t seem likely right now. People seem to like their Priuses. (Image from Toyota’s marketing site.)

Publicly-traded stocks

The other way to invest the money in a big corporation is to literally buy a part of the corporation, i.e. its stock. Stock is a lot more risky:

-

Unlike loans—where the interest rate is agreed-upon up-front—the return of a stock depends solely on what people are willing to pay you for it later.2

-

If a company goes bust, stockholders get nothing. The money you paid for your stock is used to pay the company’s debts.

Still, if you’re willing to leave your money in for longer and ride out the times when the sale price is low, it’s a solid investment.

The best idea is to buy a bunch of stock from many different companies so that the winners compensate for the losers. Buy stock in all of the top 500 companies in the US, and you get about a 10% return per year on average.3

Though be warned: in any individual year the return could be as high as 40% or as low as -40%!

Okay, but what if you still want more risk, and more reward? Time to get especially weird.

Private companies and venture capital

Public stocks aren’t good enough for you? Look for companies that might become big in the future. Invest in entrepreneurs starting small companies that might take over the market in the future.

Individually, those entrepreneurs are almost certain to fail. 90% of startups go bust. But if you invest in enough of them, the winners will (hopefully!) outweigh the losers.

Data on returns is harder to come by, but at least one report4 says that the best venture capital firms get 15% to 27% returns per year, while the worst ones get low single digits, or even negative.

Crypto and weird venture capital

But there’s a catch: the startups with obviously good ideas likely already have a lot of investors clamouring for them, putting you in a bidding war.

So Paul Graham, one of the most successful venture capitalists, says that you have to be willing to invest in companies that, at a glance, seem like bad ideas:

[…] the best startup ideas seem at first like bad ideas. I’ve written about this before: if a good idea were obviously good, someone else would already have done it. So the most successful founders tend to work on ideas that few beside them realize are good. Which is not that far from a description of insanity, till you reach the point where you see results.

Keep this in mind every time you see venture capitalists funding something that seems weird and/or stupid, from bad/fraudulent startups like Juicero and Theranos to questionable/weird investments like crypto and NFTs. It’s really hard to differentiate a good idea that seems bad from an actual bad idea.

The higher returns you want, and the higher risk you can tolerate, the weirder you have to go with your investments!

What about when interest rates change?

We went all the way up the risk ladder from government loans at the bottom to crypto at the top. What happens when the bottom shifts?

Higher interest rates means investors pick safer bets

Picture yourself as an investor in the 2010s. Government interest rates are paying almost nothing. Corporate bonds are only slightly better. You could throw your money in the overall stock market, but if you’re a professional investor, you’re likely trying to beat the stock market.

The result? Only investors looking for totally risk-free investments bother with government bonds. Everyone else has to climb a few rungs up the ladder the returns they want, which leaves plenty of money for the weird stuff at the top.

In the 2020s, after the pandemic lifts, you notice governments raise interest rates. Suddenly, you notice you can get 4% on the safest possible investment in the country. What would you do?

All else being equal, you’d likely shift your investments to safer stuff.

-

Why bother with those old 2–3% corporate bonds when a government bond pays 4%? Buy the government bonds instead.

-

To compete, companies end up having to issue new corporate bonds with higher interest rates. This sucks some money out of stocks.

-

Stocks, now losing value, get cheaper, which sucks some of the money out of venture capital.

-

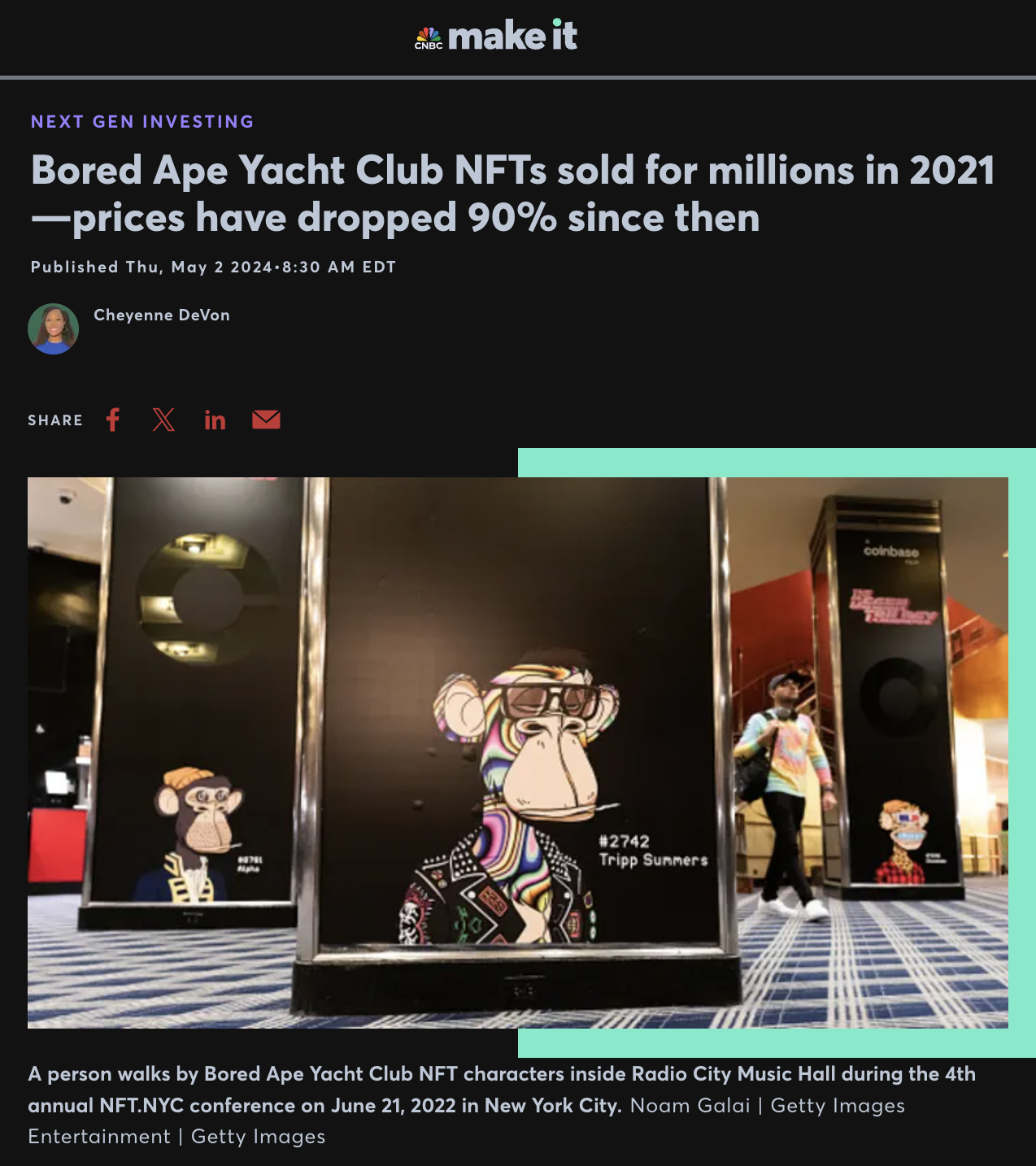

And the weird stuff—crypto, NFTs, strange startups, the stuff the internet might call a “ZIRP”—all crater.

Headline from this CNBC article.

A lot of tech startups—even sane ones—are funded by venture capital long before they start making a reliable profit. When that money dries up, it hurts their ability to pay their expenses, including tech worker salaries.

This has knock-on effects on the rest of the tech economy. Startups buy things too: they buy software to run their businesses, they pay for ad space on popular websites, they rent office space in San Francisco, etc. When they lose money, so do all the businesses serving them.

Higher interest rates make it harder to borrow money

When a company wants to fund a project but doesn’t have cash on hand, it has two major choices: it can sell stock, or it can take out a loan.

For reasons discussed above, selling stock gets harder when the government raises interest rates. What about loans?

To attract investors, its loans have to beat the government rate, often by a lot. When the government rate is near-zero, corporate loans are cheap to pay back. When they’re high? It’s expensive.5

So companies cut back. They avoid borrowing money, and they stretch what money they already have.

- They might avoid investing into more speculative or risky projects.

- They might cut back on ad campaigns that are less likely to bring huge returns.

- They might lay off entire divisions, if those divisions aren’t making them enough money to justify the costs.

If you’ve been in a tech company in the past few years, this should all sound pretty familiar to you.

Higher interest rates means less money floating around in the economy

If it causes so much damage, why does the government ever raise rates?

The big reason is to control the supply of money floating around.

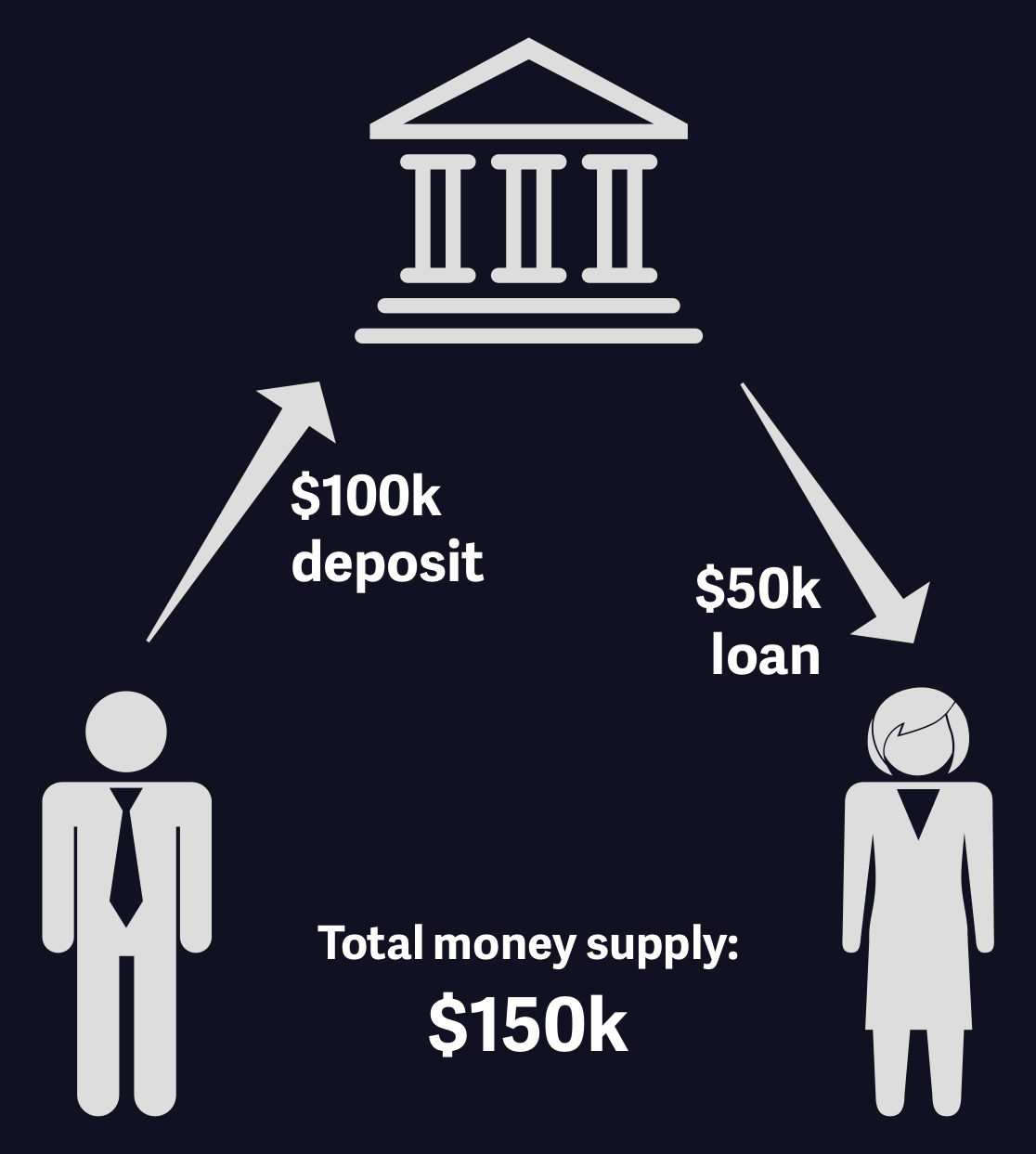

Imagine John deposits $100k into the bank. The bank assumes John probably isn’t going to want all his money back at once6, so the bank loans out $50k to Jill for use in her coffee shop.

There is now $150k floating around in the economy! Instead of the money just sitting under John’s mattress, where it wasn’t going to be of any use, it’s now being used by Jill to buy coffee beans for her lattes. The bank has effectively increased the money supply!

Unintuitive as it is, this is the foundation of all modern economies.

When government interest rates rise, fewer loans happen. That means less money floating around, which makes that money more valuable.

Inflation is the opposite of this, where money gets less valuable over time. So raising rates suppresses inflation.

Back in 2020, most governments wanted to encourage people to spend money and keep the economy running during the pandemic. They cut interest rates and even mailed cheques to people, increasing the money supply, leading to inflation. The high interest rates of today are an attempt by those same governments to clean up after themselves.

Raising rates is not a pretty solution. Starving the economy of money to fix inflation is a bit like starving someone of food to lose weight. Businesses are forced to bring prices down because people literally do not have the money to pay high prices. It works, and is the right thing to do, but it hurts.

And it’s another big reason why people aren’t spending money on frivolities like Bored Ape NFTs these days.

How this affects tech workers

Getting back to the subject of tech workers, what does rising interest rates mean for them concretely?

-

If you work for a big company and are paid in partially in stock, your stock’s value—and thus your compensation—is likely to be lower.

-

Smaller companies often look to those bigger companies to set the standard for compensation, so they might also cut pay or even do layoffs.

-

Startups have a harder time getting funding from venture capitalists. They might cut costs, take funding at a reduced valuation, or shutter entirely.

-

Most companies see reduced spending by their customers, in both consumer and business markets, as both tighten their belts.

-

Advertising is usually hit hard, as it’s one of the easiest things to cut on short notice. And a big chunk of the tech industry is funded by advertising revenue.

-

And if you’re working on a weird or risky startup that was reliant on crazy investors holding their nose and betting on you? God help you.

I’ve seen basically all of these happen to me and my friends over the past few years. I’m personally doing okay: I kept my job, but had to suffer through the cancellation of some projects I was really excited about. Some friends were less lucky.

In the broad scheme of things, this may not be a bad thing: the tech industry of the 2010s was often unnecessarily extravagant. A bunch of weird and even fraudulent crap was drowning in VC money. This might be a necessary correction.

But if you were riding that wave, I hope you kept your head above water as it crashed.

-

Sometimes you see “ZIRP” standing in for “Zero Interest Rate Policy” instead. Same difference. ↩︎

-

To be clear, you can sell bonds/loans to someone else if you need the money early, which makes it subject to market prices as well. I’m ignoring this for the sake of simplicity. ↩︎

-

Note that none of the numbers we’re talking about here are adjusted for inflation. ↩︎

-

The article’s link to the report is dead, but I found the original PDF here. The numbers in question are in page 13, if you’re curious. Unfortunately, I can’t quite tell if these are inflation-adjusted. ↩︎

-

If you recently signed a mortgage, you’ve probably experienced this shift first-hand. You also have to attract investors to loan you the money! ↩︎

-

Even if he did want all of his money back suddenly, they can usually cover that from other customers’ deposits. The only real risk is if all of their customers suddenly withdraw their money all at once. ↩︎

Forgot password?

Close message

Subscribe to this blog post's comments through...

Subscribe via email

SubscribeComments

Post a new comment

Comment as a Guest, or login:

Connected as (Logout)

Not displayed publicly.

Comments by IntenseDebate

Reply as a Guest, or login:

Connected as (Logout)

Not displayed publicly.